Doula, master's of public health graduate, new IBCLC, and feminist. I'm reflecting on my studies, reflecting on other people's studies, posting news, telling stories, and inviting discussion on reproductive health from birth control to birth to bra fitting.

Friday, February 27, 2009

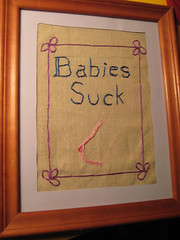

Babies Suck!

My friend Renee just sent me a fabulous birthday present - I had to share. Now the only question is where to hang it? I need someplace where I can put up a shelf of my doula books and hang this just above.

Why to choose your place of birth carefully

The Unnecesarean discusses a new c-section report out of Massachusetts. She has some great commentary, including on the claim that the hospital network with the highest cesarean rates does c-sections mainly because of problems like a big baby or "the shape of the mother's pelvis". Ah! There's the problem! All the funny-shaped pelvis women must have signed up to give birth at those hospitals!

Take a look at the list, too, and scroll from top (highest c-section rates) to bottom (lowest). First, notice how long it takes to get to facilities that are even below 30%. Second, notice how big the difference is between top and bottom. Now think: what are your chances of having a vaginal birth at the ones at the top of the list and the ones at the bottom?

If it ever sounds like I'm driving these points into the ground, it's because I am always amazed myself: half of the women you meet who had a c-section didn't need one. But they were told, and still think, they did - and when you hear their stories after the fact, it's so hard to tell who really needed it and who would have had a vaginal birth if they were at a different hospital, with a different provider. But it's a virtual guarantee that if you scooped up a handful of the women from the highest-rate hospital and put them at the lowest - funny-shaped pelvises and all! - some of those women would have a vaginal birth who wouldn't have otherwise.

How can we make women's medical care so randomly and hugely dependent on where they give birth?

Take a look at the list, too, and scroll from top (highest c-section rates) to bottom (lowest). First, notice how long it takes to get to facilities that are even below 30%. Second, notice how big the difference is between top and bottom. Now think: what are your chances of having a vaginal birth at the ones at the top of the list and the ones at the bottom?

If it ever sounds like I'm driving these points into the ground, it's because I am always amazed myself: half of the women you meet who had a c-section didn't need one. But they were told, and still think, they did - and when you hear their stories after the fact, it's so hard to tell who really needed it and who would have had a vaginal birth if they were at a different hospital, with a different provider. But it's a virtual guarantee that if you scooped up a handful of the women from the highest-rate hospital and put them at the lowest - funny-shaped pelvises and all! - some of those women would have a vaginal birth who wouldn't have otherwise.

How can we make women's medical care so randomly and hugely dependent on where they give birth?

Women who breastfeed? "Sows"

A right-wing radio host in Milwaukee lets us all know that it's ridiculous to pass a law protecting women who breastfeed in public. Because mothers are "sows" - oh wait, they're "adamant sows" (damn these uppity women) - who insist on this "crude practice". How very, very lovely.

It's always a quick, invigorating slap to the face to see how quickly right-wing types, when feeling even the slightest bit threatened, run to dehumanize women by turning them into animals (or body parts, or ugly hags...) "What do we need feminism for? Women and men are equal now!" Uh-huh.

It's always a quick, invigorating slap to the face to see how quickly right-wing types, when feeling even the slightest bit threatened, run to dehumanize women by turning them into animals (or body parts, or ugly hags...) "What do we need feminism for? Women and men are equal now!" Uh-huh.

Thursday, February 26, 2009

Happy birth story

A while back my friend e-mailed me to thank me for posting a link to a story about a pelvis that seemed too small - and wasn't.. She said, "It's nice to see that sometimes things go well!" Ever since then I've been conscious of wanting to balance the negative with the positive. It's easy to go negative - it's easy to see all the things wrong in the world and want to point them out so someone can fix them. I think I also have a feeling of wanting to warn people - "Watch out, this could happen! Or this! Or this!"

But of course I also want to inspire people with what can go right! So when I ran across this very happy (VBAC!) birth story, I thought it would be nice to share.

But of course I also want to inspire people with what can go right! So when I ran across this very happy (VBAC!) birth story, I thought it would be nice to share.

Questioning the elective c-section

I have a few concerns about what's presented as fact by a mother interviewed about her elective cesarean delivery. Chief among them is that she asserts that because her baby was breech she would have "ended up with an emergency C-section and that's the thing you want to avoid".

That's just not true. Leaving aside the option of vaginal breech birth (difficult to arrange in terms of finding a provider, but not some kind of anatomical impossibility and very common elsewhere in the world) a known breech is not going to end in an emergency c-section. One of two things will happen: 1) the mother has a scheduled c-section before going into labor or 2) the mother goes into labor before her scheduled surgery, goes to the hospital, and has a c-section. Neither of these scenarios involve an "emergency" c-section. (I was also puzzled by her reference to a doctor in an emergency c-section not always being able to do a low transverse ("bikini line") incision. Does anyone know about this? I've heard of doctors cutting a classical incision for other reasons, but not emergency-related.)

The reference to differentiating between risk in planned and emergency c-sections is also not really accurate. Even studies that control for whether or not the cesarean was indicated based on risk have found a difference between cesarean and vaginal births.

Finally, I was struck by comments like "You don't have these awful stitches 'down there'" (I guess "inside and outside your abdomen" is better?) as if women are guaranteed tearing and/or an episiotomy at a vaginal birth.

I'm happy that this woman had a positive outcome from her elective cesarean section, but that doesn't change that cesarean section is riskier than vaginal birth. At the end they ask if she would have another elective c-section for future children, and she says "Absolutely!" While you could argue that the absolute difference in risk between c-section and vaginal delivery at the first birth is small, it is undeniably true that the gap grows with every subsequent c-section. Women planning to have multiple children should in particular think hard about choosing a cesarean.

That's just not true. Leaving aside the option of vaginal breech birth (difficult to arrange in terms of finding a provider, but not some kind of anatomical impossibility and very common elsewhere in the world) a known breech is not going to end in an emergency c-section. One of two things will happen: 1) the mother has a scheduled c-section before going into labor or 2) the mother goes into labor before her scheduled surgery, goes to the hospital, and has a c-section. Neither of these scenarios involve an "emergency" c-section. (I was also puzzled by her reference to a doctor in an emergency c-section not always being able to do a low transverse ("bikini line") incision. Does anyone know about this? I've heard of doctors cutting a classical incision for other reasons, but not emergency-related.)

The reference to differentiating between risk in planned and emergency c-sections is also not really accurate. Even studies that control for whether or not the cesarean was indicated based on risk have found a difference between cesarean and vaginal births.

Finally, I was struck by comments like "You don't have these awful stitches 'down there'" (I guess "inside and outside your abdomen" is better?) as if women are guaranteed tearing and/or an episiotomy at a vaginal birth.

I'm happy that this woman had a positive outcome from her elective cesarean section, but that doesn't change that cesarean section is riskier than vaginal birth. At the end they ask if she would have another elective c-section for future children, and she says "Absolutely!" While you could argue that the absolute difference in risk between c-section and vaginal delivery at the first birth is small, it is undeniably true that the gap grows with every subsequent c-section. Women planning to have multiple children should in particular think hard about choosing a cesarean.

Wednesday, February 25, 2009

Post-screening high

Along with some other students, I'm helping start a group on our campus to support and promote breastfeeding and to raise awareness of its relationship to the reproductive continuum. (Don't worry, our name is shorter than all that!) Our first event was a screening tonight of "The Business of Being Born".

I was so excited about doing this movie at school. I wanted to show this movie to public health (and other health sciences) students for a couple of reasons. First was to counter the medical model we hear about in regards to birth. Especially studying international maternal health, we hear only about the lack of medical care. I think the impression given is that what we need is more of the kind of care we have in U.S. While that care would do a lot of good in developing countries, there are other models that could serve them even better. "The Business of Being Born" does a great job at showing what these alternatives look like.

Second, public health students are mostly young women. In maternal and child health it's about 99%! Some of these women never plan to have children, or have already had children. But for those who do, this can be a great first step into exploring birth alternatives, years before they actually become pregnant. (And, planning on babies or not, everyone knows someone who will give birth. I think we all owe it to our society to educate ourselves about safe, gentle birth so that we can support every mother in experiencing it.)

We had a great panel afterwards. We had a midwife who works in a public health setting, a hospital lactation consultant, a Bradley method teacher, a mother who has given birth to both of her children at a birth center, and me - I was honored to represent a doula perspective. I got a chance to say that I like to show this movie to young women because we are taught about birth all our lives. We are taught by movies and "reality" shows that overdramatize it, by horror stories, by rumors and half-truths. It's not that 9 months of pregnancy is too short to learn about birth - it is too short to UNlearn.

If you have not seen this movie, please do! It's not perfect (and we discussed some critiques of it in the panel) but it's a great start to that unlearning.

I was so excited about doing this movie at school. I wanted to show this movie to public health (and other health sciences) students for a couple of reasons. First was to counter the medical model we hear about in regards to birth. Especially studying international maternal health, we hear only about the lack of medical care. I think the impression given is that what we need is more of the kind of care we have in U.S. While that care would do a lot of good in developing countries, there are other models that could serve them even better. "The Business of Being Born" does a great job at showing what these alternatives look like.

Second, public health students are mostly young women. In maternal and child health it's about 99%! Some of these women never plan to have children, or have already had children. But for those who do, this can be a great first step into exploring birth alternatives, years before they actually become pregnant. (And, planning on babies or not, everyone knows someone who will give birth. I think we all owe it to our society to educate ourselves about safe, gentle birth so that we can support every mother in experiencing it.)

We had a great panel afterwards. We had a midwife who works in a public health setting, a hospital lactation consultant, a Bradley method teacher, a mother who has given birth to both of her children at a birth center, and me - I was honored to represent a doula perspective. I got a chance to say that I like to show this movie to young women because we are taught about birth all our lives. We are taught by movies and "reality" shows that overdramatize it, by horror stories, by rumors and half-truths. It's not that 9 months of pregnancy is too short to learn about birth - it is too short to UNlearn.

If you have not seen this movie, please do! It's not perfect (and we discussed some critiques of it in the panel) but it's a great start to that unlearning.

Tuesday, February 24, 2009

Childbirth ed via crochet

I love this! It's a childbirth crochet doll giving birth (and baby, cord, and placenta). I'm a crocheter and am now eyeing it and wondering if I could figure out how to replicate something similar.

Friday, February 20, 2009

Time Magazine covers VBAC

Via The Unnecessarean, Time Magazine covers the disappearing VBAC. Even more amazingly, they do a pretty good job of it! My favorite quote is this: "How can a hospital say it can handle an emergency C-section due to fetal distress yet not be able to do a VBAC?"

Yeah, how can they? "It's so much safer to be in a hospital where they can do a crash c-section!" So why do hundreds and hundreds of hospitals deny women VBACs on the grounds that they couldn't do a c-section quickly enough in an emergency?

I do wish the article had discussed how avoiding common interventions like pitocin can decrease the (tiny) risk for uterine rupture even more.

Yeah, how can they? "It's so much safer to be in a hospital where they can do a crash c-section!" So why do hundreds and hundreds of hospitals deny women VBACs on the grounds that they couldn't do a c-section quickly enough in an emergency?

I do wish the article had discussed how avoiding common interventions like pitocin can decrease the (tiny) risk for uterine rupture even more.

Australian maternity units "herding yards"

What a lovely image! This news article discusses some of the problems in Australian maternity wards, including the fact that women have to bring their own hot packs and bathtub plugs, but can get free epidurals and IV medications. Way to be cost-conscious there.

Tuesday, February 17, 2009

Breastfeeding: shattered expectations

I just finished a reading for my breastfeeding class called "Shattered expectations: when mothers' confidence in breastfeeding is undermined". I have my critiques of it (mostly that I couldn't understand some parts.) Still, there were some interesting points they made, coming out of a metasynthesis of seven qualitative studies. Here are a few things that struck me as very true:

1) There are different discourses that take place around breastfeeding. One is a "breastfeeding is natural" discourse. It's natural - our species would have died out long ago if breastfeeding wasn't so darn easy! This discourse hides the ways that breastfeeding has historically been taught and learned, and the focus is on the mother's responsibility to do what's "natural".

Another discourse is the female body as machine. The breastfeeding woman is an isolated unit, a body. Her machine might function, but it will definitely need a lot of monitoring and repair. This leads to an intense (often medical) focus on timing, duration, and amount of breastfeeding - things you can measure. It also undermines a mother's confidence.

2) With these discourses interacting, women feel isolated and guilty when breastfeeding "fails". If breastfeeding doesn't come "naturally", what does that say about her body? I had a social worker who works on postpartum depression tell me she thought some women who had serious breastfeeding problems experienced gender identity crisis. If woman=mother=natural breastfeeding ability, is someone who can't breastfeed still a woman?

In so many ways in our society, we set women up to "fail" at breastfeeding. What puts women at risk of having trouble with breastfeeding? Cesareans, 1/3 of all mothers get them, check! Medications during labor, almost universal, check! Poor support in the hospital, check! No home visitors to support breastfeeding, check! Little breastfeeding training for doctors, check! Short maternity leaves, check!

But when breastfeeding doesn't work out, what do we hear women say? "I guess I just can't make enough milk", "Breastfeeding just didn't work out for me", "I was in so much pain and I felt guilty about stopping, but I just couldn't take it anymore". It makes me so sad to hear women say these things. Yes, individuals can overcome many of the barriers society puts in place and breastfeed. But why should we make it so they have to, and why should women blame themselves when they can't?

1) There are different discourses that take place around breastfeeding. One is a "breastfeeding is natural" discourse. It's natural - our species would have died out long ago if breastfeeding wasn't so darn easy! This discourse hides the ways that breastfeeding has historically been taught and learned, and the focus is on the mother's responsibility to do what's "natural".

Another discourse is the female body as machine. The breastfeeding woman is an isolated unit, a body. Her machine might function, but it will definitely need a lot of monitoring and repair. This leads to an intense (often medical) focus on timing, duration, and amount of breastfeeding - things you can measure. It also undermines a mother's confidence.

2) With these discourses interacting, women feel isolated and guilty when breastfeeding "fails". If breastfeeding doesn't come "naturally", what does that say about her body? I had a social worker who works on postpartum depression tell me she thought some women who had serious breastfeeding problems experienced gender identity crisis. If woman=mother=natural breastfeeding ability, is someone who can't breastfeed still a woman?

In so many ways in our society, we set women up to "fail" at breastfeeding. What puts women at risk of having trouble with breastfeeding? Cesareans, 1/3 of all mothers get them, check! Medications during labor, almost universal, check! Poor support in the hospital, check! No home visitors to support breastfeeding, check! Little breastfeeding training for doctors, check! Short maternity leaves, check!

But when breastfeeding doesn't work out, what do we hear women say? "I guess I just can't make enough milk", "Breastfeeding just didn't work out for me", "I was in so much pain and I felt guilty about stopping, but I just couldn't take it anymore". It makes me so sad to hear women say these things. Yes, individuals can overcome many of the barriers society puts in place and breastfeed. But why should we make it so they have to, and why should women blame themselves when they can't?

AmeriCorps doula opportunities

As I said in my recent post, I wish more people knew about the opportunity to do maternal and child health work in AmeriCorps! (Still, I only found my job because I stumbled across it in the course of a massive AmeriCorps job search, so I understand why more people don't know about it.) There are amazing benefits to working for a good AmeriCorps program, not least of which is that your training is free. AmeriCorps programs are used to hiring people with relatively little training (although relevant experience doesn't hurt), so you are getting a huge resume's worth of experience for nothing up front. I became a Certified Doula and a Certified Breastfeeding Educator through my program. A good program (note that not all programs are good!) will also offer professional development opportunities, extra trainings, and opportunities to explore careers that are of interest to you. (AmeriCorps also offers you the opportunity to qualify for food stamps, although not everyone counts this as a plus.)

The program I worked for was part of the Community HealthCorps (not to be confused with the National Health Service Corps, which is for medical professionals with a clinical degree). Here's a list of the program locations, all located at federally funded community health centers. When I last knew - and this knowledge is several years old, so it may no longer be totally inaccurate - there were doula programs at the sites in Brooklyn, Denver, Seattle and Providence (although I no longer see the Providence site on the list, so sadly it may have closed). There was certainly discussion of training more, but I don't know if they have.

If you have any interest in health, some of these programs are great opportunities to get more experience. Some are aimed more at high school grads, others at college grads. My best advice, if you're looking, is to treat AmeriCorps the same way as you would treat any other job search. Look hard at the job, the supervisors, the program before you accept it. These programs are only as good as the organizations who run them, and since you're not going to get much money out of it you should be getting a great experience!

Edited to add, January 2011: After almost two years, I'm pleased that people are still finding this post and getting inspired by the opportunity to become a doula through AmeriCorps! Sometimes people e-mail me to ask for more information about doing one of these programs. While I am happy to talk to you about my experiences, I am now many years out of the program and don't know anything about the current programs available.

If you're interested in finding AmeriCorps doula programs, I suggest you try the following options:

1) Take a look at the Community HealthCorps link above and try to contact individual programs, or contact the Community HealthCorps national office directly;

2) Search the AmeriCorps program website for opportunities - unfortunately they don't seem to give you the option of keyword-searching program descriptions, so you would need to drill down looking for health-related programs and read through their descriptions to find ones that do maternal and child health/doula services.

The fastest and simplest way is probably to contact the national office directly; I encourage you to encourage them to make this information more easily accessible on the web! I would love to be able to link to a resource page with updated info on all of the programs.

The program I worked for was part of the Community HealthCorps (not to be confused with the National Health Service Corps, which is for medical professionals with a clinical degree). Here's a list of the program locations, all located at federally funded community health centers. When I last knew - and this knowledge is several years old, so it may no longer be totally inaccurate - there were doula programs at the sites in Brooklyn, Denver, Seattle and Providence (although I no longer see the Providence site on the list, so sadly it may have closed). There was certainly discussion of training more, but I don't know if they have.

If you have any interest in health, some of these programs are great opportunities to get more experience. Some are aimed more at high school grads, others at college grads. My best advice, if you're looking, is to treat AmeriCorps the same way as you would treat any other job search. Look hard at the job, the supervisors, the program before you accept it. These programs are only as good as the organizations who run them, and since you're not going to get much money out of it you should be getting a great experience!

Edited to add, January 2011: After almost two years, I'm pleased that people are still finding this post and getting inspired by the opportunity to become a doula through AmeriCorps! Sometimes people e-mail me to ask for more information about doing one of these programs. While I am happy to talk to you about my experiences, I am now many years out of the program and don't know anything about the current programs available.

If you're interested in finding AmeriCorps doula programs, I suggest you try the following options:

1) Take a look at the Community HealthCorps link above and try to contact individual programs, or contact the Community HealthCorps national office directly;

2) Search the AmeriCorps program website for opportunities - unfortunately they don't seem to give you the option of keyword-searching program descriptions, so you would need to drill down looking for health-related programs and read through their descriptions to find ones that do maternal and child health/doula services.

The fastest and simplest way is probably to contact the national office directly; I encourage you to encourage them to make this information more easily accessible on the web! I would love to be able to link to a resource page with updated info on all of the programs.

How to overmonitor birth even more than we already do!

I wanted to highlight a little bit of ridiculousness I found out about via Birth Activist's great post on Creepy obstetric and childbirth technology patents. Introducing...the Birth Track!

Let's discuss a few things on the Birth Track website.

First, "Currently, cervical dilatation and head station are assessed by the physician/midwife manually during vaginal examination. In the usual procedure vaginal examinations are performed numerous times during normal labor."

As Birth Activist so succinctly puts it, the alternative would be to do fewer vaginal exams. Furthermore, what are the problems with numerous vaginal exams? 1) they're uncomfortable for the mother; 2) they increase the risk of infection; 3) they can make people nervous about "lack of progress". Given that the monitors in question are attached to the cervix I can't imagine how numbers 1 & 2 will be improved, and I think 3 would be made even worse.

"The cervical dilatation measurements are performed by a small Ultrasound unit, that is placed on your abdomen, similar to the fetal monitor belt. Also three sensors are attached: two to the cervix and another one which is incorporated into the fetal scalp electrode."

I love how they try to downplay the fact that the monitor is attached to your cervix. "It's monitored by an external monitor! Also 3 internal ones." Note how they assume your water is (has been artificially) broken so you can use a fetal scalp electrode. Oh, wait, note how they assume that you'll be using a fetal scalp electrode (it screws into the top of the baby's head).

"You will have continuous information regarding the progress of labor and you will know the position of your baby every second."

Fabulous! Because continuous information has been proven to improve outcomes. Oh wait - it hasn't? It's been proven to do nothing, except increase the number of unnecessary c-sections? Oh.

"Your partner will be able to be an active participant in the labor process as he/she follows the progress of the partogram on the screen next to your bed."

Being an active participant because you watch labor progress on screen is like being an actor because you watch TV. It's a sad comment on what we think "active participation" in labor is.

Let's discuss a few things on the Birth Track website.

First, "Currently, cervical dilatation and head station are assessed by the physician/midwife manually during vaginal examination. In the usual procedure vaginal examinations are performed numerous times during normal labor."

As Birth Activist so succinctly puts it, the alternative would be to do fewer vaginal exams. Furthermore, what are the problems with numerous vaginal exams? 1) they're uncomfortable for the mother; 2) they increase the risk of infection; 3) they can make people nervous about "lack of progress". Given that the monitors in question are attached to the cervix I can't imagine how numbers 1 & 2 will be improved, and I think 3 would be made even worse.

"The cervical dilatation measurements are performed by a small Ultrasound unit, that is placed on your abdomen, similar to the fetal monitor belt. Also three sensors are attached: two to the cervix and another one which is incorporated into the fetal scalp electrode."

I love how they try to downplay the fact that the monitor is attached to your cervix. "It's monitored by an external monitor! Also 3 internal ones." Note how they assume your water is (has been artificially) broken so you can use a fetal scalp electrode. Oh, wait, note how they assume that you'll be using a fetal scalp electrode (it screws into the top of the baby's head).

"You will have continuous information regarding the progress of labor and you will know the position of your baby every second."

Fabulous! Because continuous information has been proven to improve outcomes. Oh wait - it hasn't? It's been proven to do nothing, except increase the number of unnecessary c-sections? Oh.

"Your partner will be able to be an active participant in the labor process as he/she follows the progress of the partogram on the screen next to your bed."

Being an active participant because you watch labor progress on screen is like being an actor because you watch TV. It's a sad comment on what we think "active participation" in labor is.

Saturday, February 14, 2009

What does a public health doula do?

One of the recent comments on my blog noted the idea of a "public health doula", and in the course of writing my reply I thought I'd talk a little bit about my training as a doula and why I chose that title for my blog.

I self-designed a major in public health, medical anthropology, and languages (mostly Spanish) as an undergraduate. I was interested in public health because of all the issues it pulls in - medical, cultural, political, environmental, and more. I wrote my senior thesis on breastfeeding, looking at it from a public health perspective and critical medical anthropology perspective, as well as doing original research. The reading and researching I did for that formed the basis for a lot of my thinking about birth, breastfeeding, and issues of motherhood, encouraging me to look at these topics from multiple perspectives. For example, what does an intervention do if we implement it on a broad scale? What does it mean to individuals medically? How does it seem to them culturally? What is the history behind it?

When I graduated from college I worked for an AmeriCorps program as a maternal/child health educator and doula. Everyone says "I didn't know AmeriCorps had doulas!" I feel so lucky to have stumbled across, and been accepted to, one of the few AmeriCorps programs that trains and provides doulas to low-income communities. It was the best job I've ever had, hands down. However, it was very different from private doula work! Every AmeriCorps doula program functions differently, but ours was an on-call service. We very occasionally met prenatally with clients who called us in advance, but more often one of the hospitals our community health center served would page us cold. Only twice in the whole year did I work with someone I'd met prenatally.

There were drawbacks to this model, but as a way to get a huge range of experience as a doula it was unmatched! I would say the majority of women who hire doulas are looking for a particular kind of childbirth experience, usually unmedicated and with as few interventions as possible. There is this idea that a doula is just there for someone with one particular need (extra support for unmedicated birth). The nurses at the hospitals we worked at understood that continuous labor support is beneficial for many more reasons. They paged us in for women who had a wide range of needs. Some examples of women I worked with: teen moms, women who had come to the hospital alone, moms whose first language wasn't English, families who just needed extra attention and support. I loved it! To me, there's no greater privilege than to be there for a woman when she is giving birth.

I know both I and the other doulas sometimes experienced gratitude out of proportion to what we "did" - sometimes we just sat there! But that's all we needed to do in some cases. To me, being a public health doula means being committed to the idea that every woman deserves caring continuous support during birth. I have done some private doula work and am excited about doing more, but there's still a very special place in my heart for being a public health doula.

Now that I'm pursuing a master's in public health, I'm also thinking about "big picture" issues and complicated questions, and learning much more about maternal and child health. When I chose the title for this blog (and I thought of a bunch) I wanted to pick something that would give me a space both for doula thoughts, for public health thoughts, and the merging of the two. I hope I'm doing OK at that!

I self-designed a major in public health, medical anthropology, and languages (mostly Spanish) as an undergraduate. I was interested in public health because of all the issues it pulls in - medical, cultural, political, environmental, and more. I wrote my senior thesis on breastfeeding, looking at it from a public health perspective and critical medical anthropology perspective, as well as doing original research. The reading and researching I did for that formed the basis for a lot of my thinking about birth, breastfeeding, and issues of motherhood, encouraging me to look at these topics from multiple perspectives. For example, what does an intervention do if we implement it on a broad scale? What does it mean to individuals medically? How does it seem to them culturally? What is the history behind it?

When I graduated from college I worked for an AmeriCorps program as a maternal/child health educator and doula. Everyone says "I didn't know AmeriCorps had doulas!" I feel so lucky to have stumbled across, and been accepted to, one of the few AmeriCorps programs that trains and provides doulas to low-income communities. It was the best job I've ever had, hands down. However, it was very different from private doula work! Every AmeriCorps doula program functions differently, but ours was an on-call service. We very occasionally met prenatally with clients who called us in advance, but more often one of the hospitals our community health center served would page us cold. Only twice in the whole year did I work with someone I'd met prenatally.

There were drawbacks to this model, but as a way to get a huge range of experience as a doula it was unmatched! I would say the majority of women who hire doulas are looking for a particular kind of childbirth experience, usually unmedicated and with as few interventions as possible. There is this idea that a doula is just there for someone with one particular need (extra support for unmedicated birth). The nurses at the hospitals we worked at understood that continuous labor support is beneficial for many more reasons. They paged us in for women who had a wide range of needs. Some examples of women I worked with: teen moms, women who had come to the hospital alone, moms whose first language wasn't English, families who just needed extra attention and support. I loved it! To me, there's no greater privilege than to be there for a woman when she is giving birth.

I know both I and the other doulas sometimes experienced gratitude out of proportion to what we "did" - sometimes we just sat there! But that's all we needed to do in some cases. To me, being a public health doula means being committed to the idea that every woman deserves caring continuous support during birth. I have done some private doula work and am excited about doing more, but there's still a very special place in my heart for being a public health doula.

Now that I'm pursuing a master's in public health, I'm also thinking about "big picture" issues and complicated questions, and learning much more about maternal and child health. When I chose the title for this blog (and I thought of a bunch) I wanted to pick something that would give me a space both for doula thoughts, for public health thoughts, and the merging of the two. I hope I'm doing OK at that!

Tuesday, February 10, 2009

HypnoBabies in the news!

I posted a few weeks ago about my HypnoDoula training and how exciting it was to learn more about hypnosis for childbirth. Now via Enjoy Birth, take a look at a television news report on moms using and teaching HypnoBabies. It's short, but it's exciting to see the very idea of peaceful birth in the mainstream media.

Sunday, February 8, 2009

What is a baby-friendly hospital/birth center?

I'm doing this week's reading for my breastfeeding class - this week we're focusing on breastfeeding programming and policy. One of our readings is about the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative. The campaign to make hospitals baby-friendly is worldwide, and in the U.S. people are, little by little, coming on board. Here are the steps:

1 - Maintain a written breastfeeding policy that is routinely communicated to all health care staff.

2 - Train all health care staff in skills necessary to implement this policy.

3 - Inform all pregnant women about the benefits and management of breastfeeding.

4 - Help mothers initiate breastfeeding within one hour of birth.

5 - Show mothers how to breastfeed and how to maintain lactation, even if they are separated from their infants.

6 - Give infants no food or drink other than breastmilk, unless medically indicated.

7 - Practice “rooming in”-- allow mothers and infants to remain together 24 hours a day.

8 - Encourage unrestricted breastfeeding.

9 - Give no pacifiers or artificial nipples to breastfeeding infants.

10 - Foster the establishment of breastfeeding support groups and refer mothers to them on discharge from the hospital or clinic

Implied in step 6 is the responsibility of the facility to purchase the formula they use. (Did you know that much of the formula available in hospitals is gratis, courtesy of pharmaceutical companies? It's a huge marketing tool for them.) If formula supplementation is medically indicated, the hospital has to buy it as they would any other medicine or nutritional supplement. They also have to "ban the bags" - no bags full of free formula and formula coupons at discharge.

Reading over the 10 steps to being baby-friendly, it seems so simple and it's so hard to imagine all hospitals wouldn't already be doing these things! It's unfortunate that we have to create special initiatives to encourage hospitals to promote health.

If you're interested in learning more about the baby-friendly hospital initiative, check out Baby Friendly USA and the international UNICEF Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative page.

1 - Maintain a written breastfeeding policy that is routinely communicated to all health care staff.

2 - Train all health care staff in skills necessary to implement this policy.

3 - Inform all pregnant women about the benefits and management of breastfeeding.

4 - Help mothers initiate breastfeeding within one hour of birth.

5 - Show mothers how to breastfeed and how to maintain lactation, even if they are separated from their infants.

6 - Give infants no food or drink other than breastmilk, unless medically indicated.

7 - Practice “rooming in”-- allow mothers and infants to remain together 24 hours a day.

8 - Encourage unrestricted breastfeeding.

9 - Give no pacifiers or artificial nipples to breastfeeding infants.

10 - Foster the establishment of breastfeeding support groups and refer mothers to them on discharge from the hospital or clinic

Implied in step 6 is the responsibility of the facility to purchase the formula they use. (Did you know that much of the formula available in hospitals is gratis, courtesy of pharmaceutical companies? It's a huge marketing tool for them.) If formula supplementation is medically indicated, the hospital has to buy it as they would any other medicine or nutritional supplement. They also have to "ban the bags" - no bags full of free formula and formula coupons at discharge.

Reading over the 10 steps to being baby-friendly, it seems so simple and it's so hard to imagine all hospitals wouldn't already be doing these things! It's unfortunate that we have to create special initiatives to encourage hospitals to promote health.

If you're interested in learning more about the baby-friendly hospital initiative, check out Baby Friendly USA and the international UNICEF Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative page.

Humanized birth

I attended a lovely birth on Friday, and have been telling people ever since "I went to a great birth on Friday!" They ask why it was so great. I came across this Marsden Wagner essay today, which helped me distill the reason down to three words: it was humanized.

"Humanized birth means putting the woman giving birth in the center and in control so that she and not the doctors or anyone else makes all the decisions about what will happen." Yes! This was exactly what happened. The midwife and nurse present for most of the labor were so respectful, so gentle, so encouraging. They gave her information and respected her choices. She was allowed to push in any position she wanted to.

"Humanized birth means maternity services which are based on good scientific evidence including evidence based use of technology and drugs." Yes! They didn't push anything on her; when they felt that something was truly important for her safety, they explained this to her and then when she consented, they did everything they could to make sure it didn't interfere with her birthing process.

"By medicalizing birth, i.e. separating a woman from her own environment and surrounding her with strange people using strange machines to do strange things to her in an effort to assist her, the woman’s state of mind and body is so altered that her way of carrying through this intimate act must also be altered and the state of the baby born must equally be altered." Everyone involved in the birth was so careful to help the woman have as undisturbed a birth as possible, and to allow her birth to occur without intervention or disruption. The lights were low, everyone spoke quietly when she was deep into her labor, she was able to labor where she wanted for however long she wanted to.

I have so infrequently seen a truly humanized birth in the hospital, but the care providers I worked with on Friday inspired me and made me believe that with the correct alignment of the stars it is possible. I only wish for more women, and more medical professionals, to experience it.

"Humanized birth means putting the woman giving birth in the center and in control so that she and not the doctors or anyone else makes all the decisions about what will happen." Yes! This was exactly what happened. The midwife and nurse present for most of the labor were so respectful, so gentle, so encouraging. They gave her information and respected her choices. She was allowed to push in any position she wanted to.

"Humanized birth means maternity services which are based on good scientific evidence including evidence based use of technology and drugs." Yes! They didn't push anything on her; when they felt that something was truly important for her safety, they explained this to her and then when she consented, they did everything they could to make sure it didn't interfere with her birthing process.

"By medicalizing birth, i.e. separating a woman from her own environment and surrounding her with strange people using strange machines to do strange things to her in an effort to assist her, the woman’s state of mind and body is so altered that her way of carrying through this intimate act must also be altered and the state of the baby born must equally be altered." Everyone involved in the birth was so careful to help the woman have as undisturbed a birth as possible, and to allow her birth to occur without intervention or disruption. The lights were low, everyone spoke quietly when she was deep into her labor, she was able to labor where she wanted for however long she wanted to.

I have so infrequently seen a truly humanized birth in the hospital, but the care providers I worked with on Friday inspired me and made me believe that with the correct alignment of the stars it is possible. I only wish for more women, and more medical professionals, to experience it.

Wednesday, February 4, 2009

Why I have to ignore the Motherlode comments section, or why breastfeeding is not a pill

I sense an imminent downturn in my posting. I am currently applying to summer internships, scholarships, and assistantships for next year. I also have several papers to write!

Before that happens, I wanted to discuss something that came up in class today. Being a public health doula is interesting. This semester I am taking a class on infant and young child feeding, taught by one of the leaders in breastfeeding policy. I thought she did an excellent job of emphasizing the difference between individual, clinical breastfeeding practice and a public health orientation towards breastfeeding. Many of the benefits we tout about breastfeeding are important, but we cannot promise them for any child. Breastfeeding is not a pill that you take and see automatic results. Your breastfed child may be much healthier than your formula-fed child, but the reverse could also possibly be true. Many efforts to promote breastfeeding dead-end in "Well, I was formula fed and I'm smart and healthy. It can't be that important." But from a public health perspective, we are looking at populations. If a child is 100% breastfed, we cannot guarantee better outcomes than a child who is 0% breastfed. But if a population of children are 100% breastfed, we can certainly guarantee better outcomes than a population that is 0% breastfed.

That's why I have to actively not read the comments section of so many Motherlode blog posts. As our professor says, "Breastfeeding is not a pill." If you breastfeed your baby, that's wonderful, but if you don't, it's not as if you withheld a magic pill. Your baby may be sick or healthy, and you can never be sure if breastfeeding did or would have made a difference. But the commenters on Motherlode are all over the "pill" thinking. If there's a post about a recent study on breastfeeding, it starts again. "My children are FINE and they had NOTHING but formula." "My children never had a DROP of formula and they NEVER had an ear infection!" "I nursed and my kid was sick a lot anyway." Etcetera.

It's not just for breastfeeding, and it's not just on Motherlode, either. Birth debates are full of studies with a sample size of one. I think stories are wonderful - as humans, we respond to them strongly. They illustrate points more strongly than numbers ever could. In the field of qualitative research, systematic interviewing is used to generate data that is often invaluable and may even be more helpful than numbers in some settings. But one person's experience is just that, and no one should make any proclamations based on it. When we aggregate many stories or the numerical results of studies, we can start seeing patterns and identifying risks and benefits. Then we can make decisions by weighing those risks and benefits. If we use stories to illustrate those or to explore them more deeply, I think that's great. But anecdotal evidence should generally be used to prove exceptions to a rule - not to prove a rule itself.

Before that happens, I wanted to discuss something that came up in class today. Being a public health doula is interesting. This semester I am taking a class on infant and young child feeding, taught by one of the leaders in breastfeeding policy. I thought she did an excellent job of emphasizing the difference between individual, clinical breastfeeding practice and a public health orientation towards breastfeeding. Many of the benefits we tout about breastfeeding are important, but we cannot promise them for any child. Breastfeeding is not a pill that you take and see automatic results. Your breastfed child may be much healthier than your formula-fed child, but the reverse could also possibly be true. Many efforts to promote breastfeeding dead-end in "Well, I was formula fed and I'm smart and healthy. It can't be that important." But from a public health perspective, we are looking at populations. If a child is 100% breastfed, we cannot guarantee better outcomes than a child who is 0% breastfed. But if a population of children are 100% breastfed, we can certainly guarantee better outcomes than a population that is 0% breastfed.

That's why I have to actively not read the comments section of so many Motherlode blog posts. As our professor says, "Breastfeeding is not a pill." If you breastfeed your baby, that's wonderful, but if you don't, it's not as if you withheld a magic pill. Your baby may be sick or healthy, and you can never be sure if breastfeeding did or would have made a difference. But the commenters on Motherlode are all over the "pill" thinking. If there's a post about a recent study on breastfeeding, it starts again. "My children are FINE and they had NOTHING but formula." "My children never had a DROP of formula and they NEVER had an ear infection!" "I nursed and my kid was sick a lot anyway." Etcetera.

It's not just for breastfeeding, and it's not just on Motherlode, either. Birth debates are full of studies with a sample size of one. I think stories are wonderful - as humans, we respond to them strongly. They illustrate points more strongly than numbers ever could. In the field of qualitative research, systematic interviewing is used to generate data that is often invaluable and may even be more helpful than numbers in some settings. But one person's experience is just that, and no one should make any proclamations based on it. When we aggregate many stories or the numerical results of studies, we can start seeing patterns and identifying risks and benefits. Then we can make decisions by weighing those risks and benefits. If we use stories to illustrate those or to explore them more deeply, I think that's great. But anecdotal evidence should generally be used to prove exceptions to a rule - not to prove a rule itself.